What Happened To The Alt Right?

The Alt Right 1.0, "whiteness" as an organising principle, its extinction and descendants.

Recently, I made a documentary style video on infamous Neo-Nazi turned gay erotica author Christopher Cantwell (you can watch it here). As many have noted, almost none of the names in Cantwell’s story have any online relevancy like they used to. This post, originally intended as a note that became too long, will consist of some personal observations of mine regarding the decline of the Alt Right.

In the mid - late 2010s, any political content creator felt the constant pressure to platform and deal with white nationalist figures, fearing the consequences of cowering from debating issues like race realism or the ethnostate. The Alt Right’s online momentum was so strong that only censorship could stop them. Today, these figures have zero influence on online discourse and anyone can talk freely about them without fear of backlash.

The Alt Right was a mostly online, white nationalist movement that ran roughly from 2014 to 2018, peaking during the early phase of Trump’s presidency. Although many current far-right influencers share an ancestor with the Alt Right, they are a different species.

Furthermore, the Alt Right emerged from the convergence of online subcultures with the aesthetics of transgression and irony that defined internet culture, but didn’t translate well with real life people or electoral politics. What began as an ironic, nihilistic movement, “trolling” liberal sensibilities, slowly transformed into a network of ideological entrepreneurs who aestheticised reactionary politics.

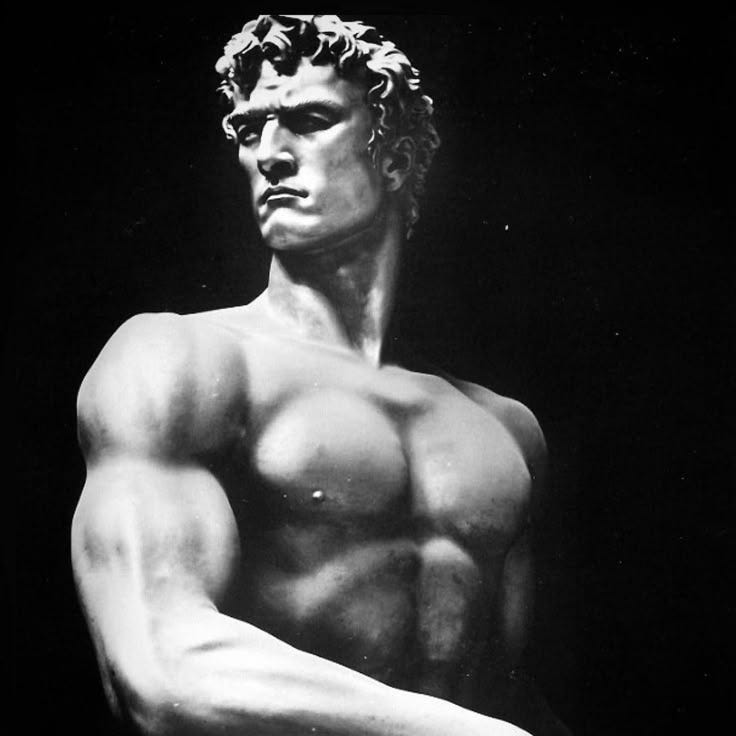

The shift “from Pepe to Greek statues” marked a symbolic move from internet irony to pseudo-intellectual romanticism: the fetishisation of “Western civilisation” and “tradition” as a counterpoint to liberal modernity. These “Save Evropa” accounts do exist today, but they are mostly faceless, belonging to a niche subculture, with few large figures leading events and appearing on podcasts, etc, unlike back in the days of the Alt Right.

Charlottesville in 2017 represented the collapse of the Alt Right. What had been performative irony online erupted into violent reality. Extremist communities value purity - and members of the community signal their belonging by espousing more and more extreme, cynical or apocalyptic points of view. Many of Unite The Right’s attendees, such as Christopher Cantwell, had been on a long process of radicalisation such that, by the time of the rally, they were shouting violence was the only answer.

Indeed, the car attack that killed Heather Heyer shattered the illusion that this was a movement of ironic memesters immune to cringe - it exposed its underlying dark triad pathology. These group dynamics that resist moderation and encourage purity spiralling and extremism creep doom a movement to fail.

The key sociological lesson is that whiteness - as an organising identity - lacks the internal solidarity or material coherence to sustain a movement in postmodern conditions. As scholars of race and nationalism (Bonilla-Silva, Kaufmann, etc.) have argued, whiteness functions as a structure of privilege rather than a lived community. For example, many people who subsume the category of “white” have different cultural and religious histories, growing up in different diasporas in different neighbourhoods, with opposing migration histories.

In modernity, “the white race” organised people around state power, capital accumulation, and civilisational mission. In postmodernity, those structures have dissolved, leaving whiteness as a hollow signifier of nostalgia without material reality. “There is no white culture”, many white people will often state. Of course, Italian, Greek, Irish, and English cultures have distinct and robust traditions,1 but these group’s shared convergence into “whiteness” was achieved through assimilation into systems of advantage. Whiteness isn’t a culture, it’s a status.

In fact, one of the tragedies of whiteness is that these groups, like Italians and Germans, through being white, lose their cultural identities and are subsumed under the a-cultural, middle class, suburban boredom of whiteness, losing what authentic traditions they had.

In contrast, something like “blackness”, which is largely defined in opposition to or by oppression from whiteness, is a more effective organising principle. Sociologists have long noted that marginality gives rise to durable social networks and symbolic cohesion, such as a need for “counterpublics” - churches, fraternal organisations, music scenes, or political movements.2

The Alt Right was partly motivated by observing black and indigenous resistance movements and misinterpreting them as forms of the same exclusionary politics they themselves espoused. In an attempt to imitate these struggles, they reframed white nationalism as a kind of “identity politics for white people.” Yet, for the above reasons, the two are not symmetrical. Most people have the political sense to differentiate between the KKK and black integrationists.

Today’s far-right subcultures have adapted. They rarely identify as “white nationalists.” Instead, they camouflage racial politics under religion, masculinity, or anti-globalism. The belief in racial hierarchy has rebranded through cultural and moral signifiers rather than biological ones. Christianity, “tradition,” and “Western values” now act as proxies for race in an attempt to re-legitimise exclusion within mainstream discourse.3 For example, one of the only surviving members of the Alt Right is Nick Feuntes, whose white nationalism has slid beneath the surface and become far more cryptic than it once was.

I could go on forever about what a fringe, pseudo-intellectual, reactive and down right stupid movement like the Alt Right got wrong. In a nutshell, “whiteness” is boring, not practical and incoherent.4 Something like The Alt Right was bound to fail. Moral sensibilities aside, the Alt Right is now remembered as an awkward and cringe moment in internet history, far from the political movement is aspired to be.

Groups that, by the way, consist of many different ethnicities, are equally defined across cultural, geographic and linguistic lines, have been historically divided, and are polysemously envoked.

Similarly, I have written a post about LGBT icon John Waters and his concept of trash culture as a legitimate existentialist philosophy, again touching on the relation between marginality and culture.

This concept of “identity by proxy” was even articulated by The Alt Right in the 2010s, who instead sought to formalise whiteness and remove these proxies from the conversation.

If you’re interested in why I’m not a nationalist, read my post Why I’m Not A Nationalist - A Genealogical Debunking Argument”.

Great points here.

Did it fail though? Most of the key folks associated with it may have disappeared, but its ideas are pretty mainstream now. Was that not the whole point?