Technofeudalism, Surveillance Capitalism, and Disciplinary Power

Technofeudalism is the economic system, surveillance capitalism is its logic of accumulation, and disciplinary power is the mode of governance it relies on.

Do you ever wonder how the economy works when we don’t really make things anymore? Most of the biggest economic actors don’t own factories… They have server rooms… As David Mitchel said; “we used to make steel”, so what gives?

Well, I have a few concepts that I like to throw around when it comes to what gives. These are Yanis Varoufakis’s concept of technofeudalism, Shoshana Zuboff’s theory of surveillance capitalism, and Michel Foucault’s framework of disciplinary power.

So firstly, technofeudalism… This describes an economic order where major technology companies control critical digital resources, like data, algorithms, and cloud infrastructure, and generate revenue through dependency rather than competitive markets.

Secondly, surveillance capitalism, as defined by Zuboff, refers to an economic system that profits from extensive collection and analysis of personal data to predict and influence human behavior.

Lastly, Foucault’s disciplinary power explains how modern societies control people not through force, but by continuously monitoring and subtly guiding behavior to produce self-regulating individuals.

I will also examine concrete examples such as real-time bidding in digital advertising, Amazon’s productivity surveillance in warehouses, Facebook’s emotional contagion experiment, and the dominance of cloud infrastructure by companies like AWS and Google.

I am going to argue that in today’s world, technofeudalism is the economic system, surveillance capitalism is its logic of accumulation, and disciplinary power is the mode of governance it relies on.

I mean… these three ideas don’t fit that neatly into a trinity… but I thought it would be cool to frame it that way nonetheless.

So, that is an overview. If you aren’t familiar with these concepts, this should be an interesting read. If you are, well… I don’t know…

Exposition:

Now, I am going to tell a story about an app…

(The twilight zone… Just in case you didn’t get the sick reference…)

Imagine if you will an app dubbed “uber for nursing” that serves as the platform for a gig economy of nurses. The app allows nurses to bid for shifts, resulting in a “race to the bottom” in which an already overworked and essential section of the labor force undercut each other for lower pay.

While also, the app demands daily “safety fees” and immediate pay charges that reduce take home earnings. Just like all gig workers, the app doesn’t provide health insurance, paid leave, job security or any other provisions for benefits offered by traditional employment.

Imagine further that the app collects extensive data on nurses, such as bidding patterns, work history and financial information. The app also employs rating systems and attendance policies that monitor and regulate nurses’ behavior. For instance, missing a shift or arriving late can result in penalties or reduced access to future work opportunities.

What’s more, this apps may determine pay using an algortihm that factors in what the nurse was willing to accept for a previous assignment, how often they bid for shifts, or even personal debts held (like credit card debt).

Well, you don’t have to imagine. This app is called “Shiftkey”. It is one of many gig nursing apps. The Roosevelt Institution published an article called “Uber for Nursing: How an AI-Powered Gig Model Is Threatening Health Care” that detailed interviews from 29 “gig” nurses, revealing that these apps contribute to worse work conditions for less pay.

(Screenshot of “Shiftkey”, where you can bid for shifts. This is when a gig-nurse might get hit with the “just get another job, bro”…)

The dependency on a single platform for work in which workers have little bargaining power really resembles a feudal economy… in which the tech overlords resemble lords and the nurses serfs…

ShiftKey’s practices seem to reflect a shift from traditional capitalist labor relations to a system characterized by centralized control, extensive data exploitation, and behavioral regulation… Almost like we are heading into a new economy that uses new and improved means of exploitation.

Speaking of which, one neat way of describing this economy is as technofeudalism.

Defining Technofeudalism:

The wonder of the free market has always been having a large number of firms furiously competing to produce the coolest knickknacks for you to consume at the highest convenience.

(Behold, the wonders of the free market.)

Technofeudalism emerges when digital platforms replace such market competition with controlled digital ecosystems, monetizing access and dependency rather than traditional production and exchange.

According to Varoufakis, these platforms extract economic rents through exclusive control of digital infrastructure, proprietary algorithms, and user data. Users and businesses must pay or conform to platform rules to gain visibility and access.

(When you think of a “free” market… Do you envision one firm controlling 40% of sales?)

For example, Amazon controls approximately 40% of all retail e-commerce sales in the United States as of 2024, extracting fees and commissions from third-party sellers at an average rate of 45%, up from 19% in 2014. While also, Apple’s 30% commission on app sales, for instance, mirrors a form of ground rent.

Basically, technofeudalist firms operate with little real competition. Instead of generating profit by producing goods or services for open markets, they extract value by controlling access to digital infrastructures and user data.

In Marxist theory, the commodity is the central economic unit of capitalism. It represents a good or service produced for exchange on the market, embodying both use-value (its practical utility) and exchange-value (its value in relation to other commodities). Capitalism, in this view, is driven by the production and circulation of commodities, with profit emerging from the exploitation of labor during production.

Technofeudalism represents a departure from this mode of economy. Rather than being concerned primarily with production and the circulation of commodities, technofeudalism is most concerned with rent extraction and making users and businesses dependent on their platforms for visibility, communication, and commerce.

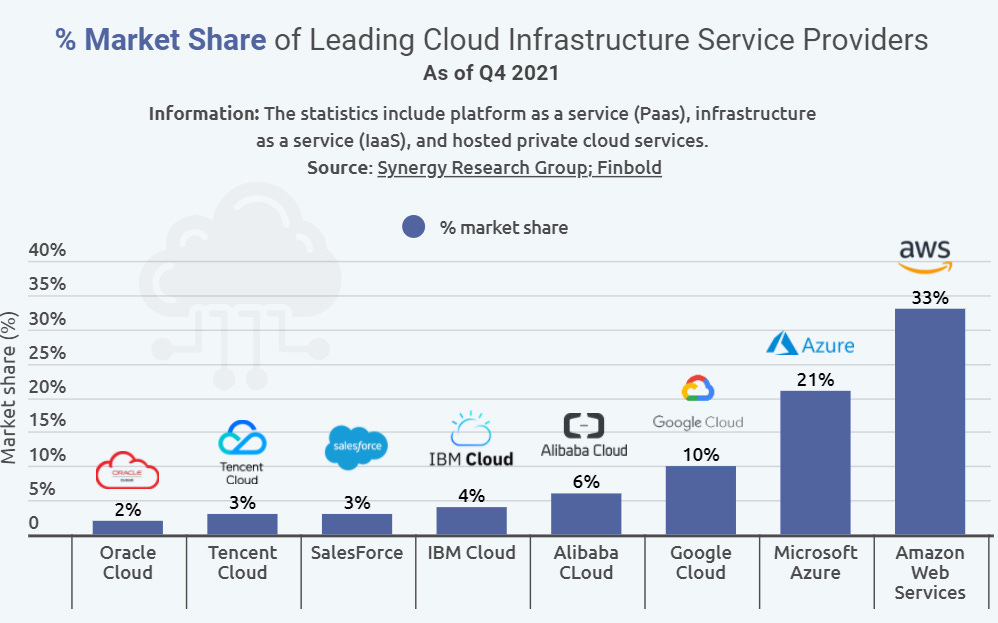

(Oh look at that… The same firm that controls 40% of retail e-commerce sales also controls a third of cloud infrasturcture…)

The cloud infrastructure market is highly concentrated. As of late 2024, Amazon Web Services (AWS) alone holds about 30–33% of global cloud infrastructure share, followed by Microsoft Azure (~20–23%) and Google Cloud (~10%). Together, these three control roughly two-thirds of the world’s cloud market, while Chinese players like Alibaba and Tencent, though dominant regionally, have single-digit global shares.

This triopoly in cloud services exemplifies how digital infrastructure is centralized under a few “cloud lords.” These platforms host private and public digital services, enforcing technical standards, pricing strategies, and service integrations that lock users into dependency. Users find exit difficult due to high switching costs and infrastructural complexity, reinforcing economic and behavioral control reminiscent of feudal obligations.

(Real photo of a “cloud lord”.)

In the mobile app economy, two firms dictate the entire landscape. Google’s Android and Apple’s iOS together account for virtually 100% of smartphone operating systems worldwide (Android ~72%, iOS ~27% as of 2024). This duopoly means Google and Apple control the gateways to mobile services and content.

Apple’s control is especially strict. All iPhone apps must go through its App Store, where Apple imposes fees and rules. Globally, Apple and Google’s operating system dominance exemplifies how digital infrastructure has replaced open marketplaces with private ecosystems. Developers and users must abide by the terms of these platform owners, effectively operating as tenants in their walled gardens.

Meta Platforms (formerly Facebook Inc.) exemplifies digital feudal power over social interaction. Meta’s “family of apps” (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger) had 3.98 billion monthly active users by early 2025, over half the world’s population. This near-universal reach, outside of a few markets like China, makes Meta a gatekeeper of social connectivity and attention.

Varoufakis notes that on platforms like Facebook, users effectively “toil” for the platform by posting content and data that Meta monetizes via advertising. In technofeudal terms, users are serfs contributing free labor (posts, photos, videos, location data) which build the platform’s capital.

Meanwhile, businesses must pay “rent” to reach those users, e.g. Facebook initially gave publishers free reach, then later throttled it to force paid advertising, a bait-and-switch dynamic that author Cory Doctorow calls “enshittification”.

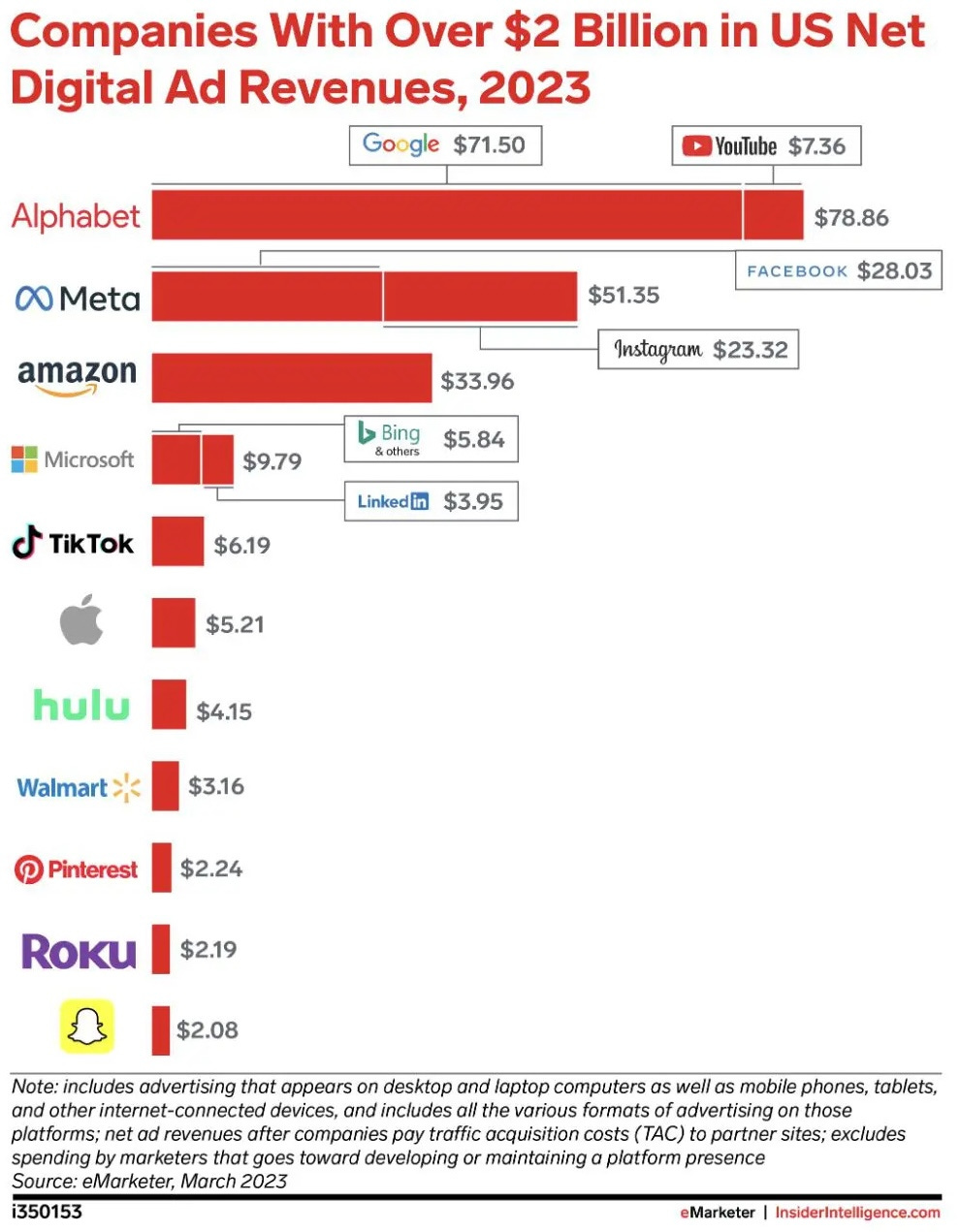

(Guys, I am just getting into this “power” thing… Is two companies controling two thirds of ad revenue able to influence society much?)

The attention market has thus been enclosed by a few platforms: for instance, together Google and Meta capture about 65% of global digital advertising revenues, reflecting how they own the audience commodity.

This dominance lets them set terms unilaterally (e.g. changes in algorithms or fees) much like feudal lords altering dues, with little recourse for dependent businesses or creators.

Many digital feudal lords use interoperability barriers to solidify their rent streams. For instance, Facebook’s dominance in social networking has been protected by its control of the social graph (users’ friend networks).

Historically, users could not export or communicate outside Facebook’s walled garden easily, forcing everyone to stay on the platform. Similarly, Google leverages its dominance in search and advertising to require use of its tools (AMP for news publishers, Google’s ad exchange, etc.), extracting data and fees.

Central to technofeudalism is the eroding of competition. The above practices are at odds with the capitalist ideal of free markets. In a nutshell, the rise of these technofeudalist structures is a shift from markets to… platforms.

Transactions that once occurred in open markets (buying goods, exchanging information, media distribution) now occur on privately controlled platforms (Amazon, Facebook, YouTube, Uber, etc.). These platforms often mimic markets in form but not in substance.

For example, Amazon’s marketplace hosts many buyers and sellers, which looks like a market, but Amazon manipulates search rankings, controls pricing rules, and can even compete against its third-party sellers with its own products, undermining the free-market dynamic. In Uber’s case, an algorithm centrally sets fares and dispatches drivers… again, it’s a centrally managed “market” where Uber holds lordly power over participants (drivers have little say in prices or terms).

(“Rent?”)

Crucially, rent, not profit, is the dominant mode of extraction in these systems. Profits in classical capitalism are earned by investing capital to produce goods/services better or cheaper than competitors. In technofeudalism, however, the biggest tech firms often sacrifice profits to gain market share, then harvest rents once they’ve locked in users/dependents.

Varoufakis notes that many platform giants prioritize maximizing user base and throughput (often running services at a loss or break-even) in order to eliminate competition, then charge rent from their captive user base. This is akin to feudal land enclosure; first capture the territory, then charge everyone who lives on it.

For example, Amazon for years reinvested earnings to dominate e-commerce and logistics; now its immense seller fee revenue is pure rent on that dominance. Likewise, Facebook and Google provide “free” services to billions, dominating attention and data, then monetize that captive audience via advertising rents.

So, that is technofeudalism. Now, that we have dealt with the prevailling economic system of current society, let us move onto surveillance capitalism… what I like to think of as the mode of accumulation…

Surveillance Capitalism:

Have you ever been talking to someone about something, then opened Instagram and seen an ad for exactly what you were just discussing? It almost feels like your phone is listening to you…

Whether or not that’s literally true, the experience is a result of how deeply and constantly you’re being surveilled… Your data, behavior, and social context are tracked so effectively that it can feel like technology is listening to you at all times…

Before, we examined Varoufakis’s concept of technofeudalism and how the circulation of commodities has been replaced with rent extraction through controlling cloud capital… Now, I am going to explain how capital accumulation has been replaced by data accumulation…

Surveillance capitalism, as articulated by Zuboff, is a new economic order where personal human experience is systematically turned into behavioral data, which companies use to predict and influence actions for profit.

Ergo, surveillance capitalism relies on extensive digital monitoring to collect vast amounts of user data, transforming our private lives into sources of revenue through predictive analytics and targeted interventions.

Zuboff argues that this process not only monetizes data but also erodes personal autonomy, as surveillance capitalism seeks to shape and control behavior by anticipating future actions and presenting tailored content that influences decision-making and consumption patterns.

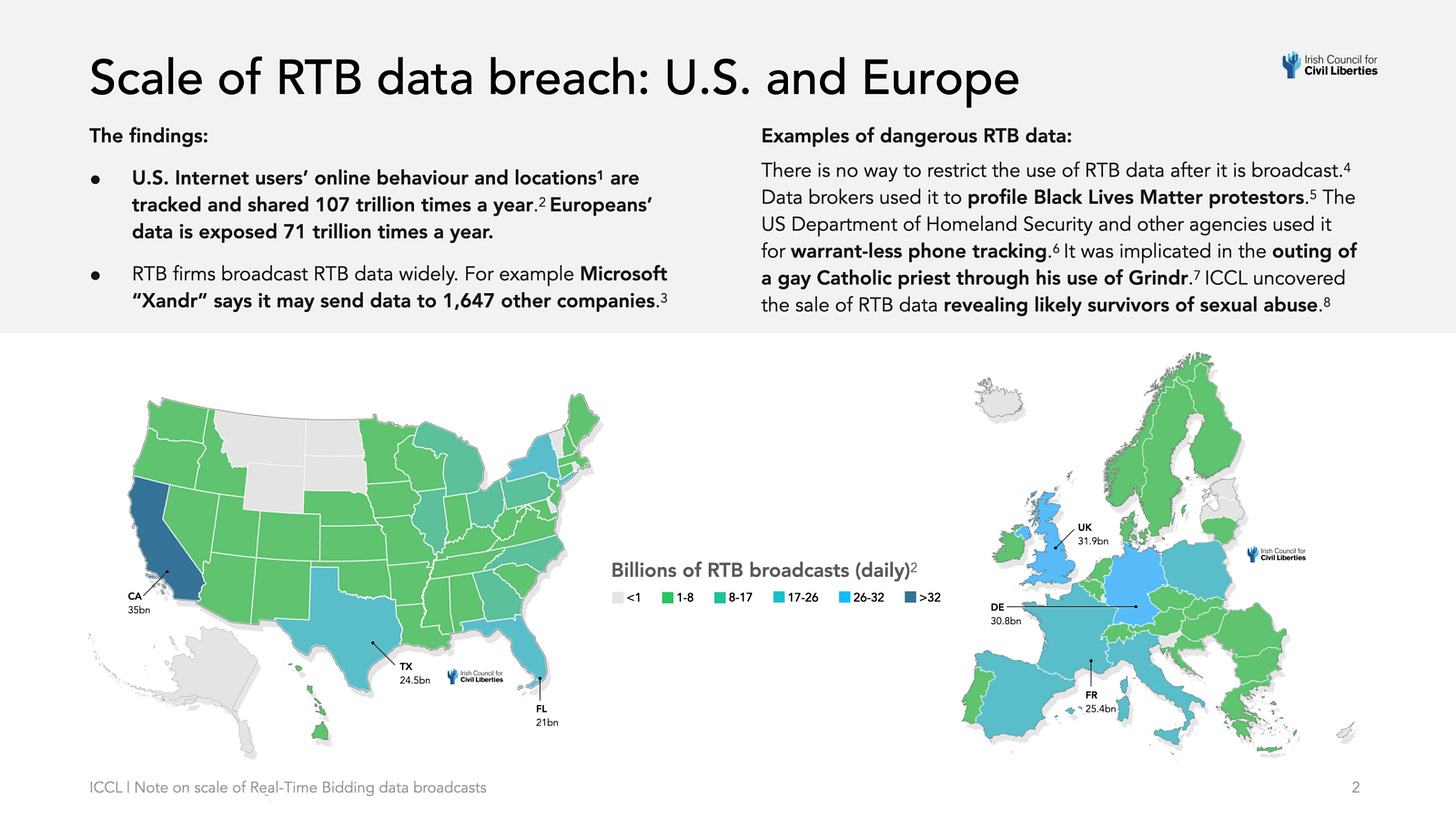

The online advertising system exemplifies surveillance capitalism’s scale. Real-Time Bidding is the technology that auctions off ad impressions (and thus user attention/data) in milliseconds every time you load a webpage or app. In order to decide which ad to show you, ad exchanges broadcast detailed information about you to hundreds or thousands of potential bidders.

(Advertising allows the tracking of your internet footprint to profile your political views…)

This happens behind the scenes for virtually every ad-supported site. A 2022 report by the Irish Council for Civil Liberties called RTB “the biggest data breach ever” due to the sheer volume of personal data leaked. The ICCL found that in the U.S. and Europe, the RTB industry tracks and shares what people do online and their location about 178 trillion times per year.

In Europe alone, personal data is broadcast to ad bidders 197 billion times per day via RTB, and in the U.S. similarly hundreds of billions of times daily. On average, a person in the United States has their online activity and location exposed 747 times per day through RTB broadcasts, while a European user’s data is exposed about 376 times per day.

These broadcasts often include identifiers, browsing history, app usage, GPS coordinates, and even inferred interests or demographics, all sent to a myriad of ad tech companies. Thousands of companies participate: Google, for instance, has 4,698 partner companies that it allows to receive RTB user data in the U.S. ad auctions.

Once broadcast, this data can be stored, combined, and used without the individual’s control. The scale is staggering and largely invisible to users, amounting to a constant auctioning of our data every time we engage with digital media.

Regulators warn that this system is effectively surveillance by design, as the U.S. Federal Trade Commission put it;

“Firms now collect personal data on individuals at a massive scale in a stunning array of contexts… business models incentivize the endless hoovering up of sensitive user data”.

The RTB-driven ad economy was valued around $117–127 billion in 2021 and continues to grow, meaning surveillance of users is deeply baked into the financial model of the internet.

(Women instinctively know that your Android phone is a means of surveilling personal data.)

Smartphones intensify surveillance capitalism by furnishing a constant stream of personal data (GPS location, contacts, messages, app usage, biometrics). Many mobile apps collect extensive data and share it with third parties (advertisers or data brokers). For instance, weather or flashlight apps have been caught siphoning location data to data brokers.

The average app can include dozens of third-party SDKs (Software Development Kits) that send user info to companies like Google, Facebook, or analytics firms. Modern “smart” devices, from voice assistants in homes to wearables, similarly feed the surveillance economy.

Zuboff notes that every “smart” or “personalized” service is actually a supply chain interface for surveillance, turning personal behaviors into data. Thus, our devices serve as always-on sensors, and the data they emit becomes a key economic resource.

Naturally, a shadow industry of data brokers aggregates and trades personal data at massive scale. These brokers collect information from numerous sources, online tracking, purchase histories, public records, and more, to build comprehensive profiles on individuals. According to testimony and research, the average data broker has thousands of data points per person on file.

For example, the leading broker Acxiom (now LiveRamp) claims to have dossiers on 2.5 billion people, each with over 3,000 distinct data points (demographics, interests, habits, etc.). Another source estimates data brokers collect on the order of 1,000–1,500 data points per person in their databases.

These profiles are sold to marketers, insurers, employers, and even political operatives. The Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2018 demonstrated how such data could be weaponized: Facebook quietly allowed a third-party app to harvest not just the user’s data but their friends’ data, ultimately yielding a trove on ~87 million people that was sold to a political consulting firm. That data was used to psychographically target voters with tailored propaganda.

This incident, for which Facebook was later fined $5 billion by the FTC, highlighted that user data itself has become a currency, traded and utilized in ways users never expected. It also showed the lack of transparency and consent inherent in surveillance capitalism: tens of millions had their personal information shared and repurposed without their knowledge.

The global digital advertising market was about $500–600 billion in 2023, and it is overwhelmingly dominated by two American companies: Alphabet (Google) and Meta (Facebook). Together, Google and Meta are expected to take in roughly 65% of worldwide digital ad revenues.

(Seriously, this whole article is basically “fuck Amazon” at this point… The disciplinary power section is even worse for them…)

If we include Amazon (a fast-growing third player in ads), the top three account for over 70% of digital ad spend. This duopoly/triopoly leaves only a small fraction of the pie to all other publishers and ad firms. Google alone, through Search ads, YouTube ads, and its ad network, earned about $224 billion in advertising in 2022 (out of Alphabet’s $283B total revenue), a testament to how lucrative personal data-driven targeting is.

Facebook (Meta) earned about $113 billion in ad revenue in 2022, nearly all from leveraging user data on its platforms. According to analysis;

“Advertising revenue and growth are overwhelmingly dominated by a handful of large U.S. and Chinese players, with the remaining 50+ firms each generating less than 1% of ad revenues”.

Chinese tech giants also play a role – e.g. Alibaba, Tencent, and Bytedance (TikTok) – especially within China’s huge internet population.

But outside China, Google and Meta essentially control the global attention market, using their surveillance-based profiles to offer advertisers finely targeted audiences. For instance, Facebook can target ads based on thousands of attributes (age, interests, behavior, “lookalike” profiles, etc.), while Google combines data from Gmail, search history, YouTube, Maps, Android phones, and more to personalize advertising.

The real-time bidding system ensures that whenever a user visits a site, these giants can instantly bid to show an ad tailored to that user’s profile, thus monetizing the data trails from surveillance. This market power also reinforces their data dominance – more ad revenue funds more data collection and AI analytics, creating a feedback loop hard for smaller entrants to challenge.

In classical capitalism, the goal was to accumulate capital by exploiting labor; under surveillance capitalism, the new object of accumulation is your data… captured, commodified, and sold without your consent.

So, we have now examined the economic structure and the mode of accumulation… Now, let us turn to the means of governance; disciplinary power.

Disciplinary Power:

When we think about power, one might envision a King or sovereign entity governing through laws and decrees, backed by the threat of violent punishment. In classical political theory, power is typically thought of as the capacity to command, prohibit or withhold, to command, punish, or take life, often symbolized by the monarch’s right to say “no”.

(no)

In contrast, Foucault’s concept of power sees power as diffuse, relational, and productive. It operates not just through prohibition but by shaping behavior, knowledge, and subjectivity.

As Foucault wrote in his text “Discipline and Punish”:

“Disciplinary power… is exercised through its invisibility; at the same time it imposes on its subjects a principle of compulsory visibility. In discipline, it is the subjects who have to be seen. It is this fact of being constantly seen, of being able always to be seen, that maintains the disciplined individual in his subjection.”

In other words, continuous surveillance (or the possibility of it) becomes a trap that assures obedience: “Visibility is a trap,” as Foucault succinctly put it . This power works by observing, examining, measuring, and correcting individuals, producing what Foucault calls “normalized” behavior.

There is an entire apparatus of hierarchical observation, normalizing judgment, and examination that defines disciplinary power . For example, hierarchical observation: teachers, supervisors, cameras keep watch; normalizing judgment: standards of performance or behavior are set, and deviations are noted as “abnormal”; the examination: tests, performance reviews, medical exams, all compile knowledge about individuals to classify and control them.

Ultimately, disciplinary power aims to produce “docile bodies”, people who behave in desired ways of their own accord, because they have internalized the surveillance and norms.

Importantly, Foucault noted that disciplinary power creates knowledge as a byproduct, statistics, records, profiles, which in turn justifies more control . He famously said “there is no power relation without the correlative constitution of a field of knowledge”. A simple example: a factory monitors worker output (knowledge) and uses it to reward or punish workers (power), thereby optimizing control.

Disciplinary power is pervasive in modern society, Foucault referred to “the judges of normality” (teachers, doctors, officials) who are everywhere, making us all constantly compare ourselves to social norms and discipline ourselves.

In biology, capillaries are the tiny blood vessels that reach every part of the body. Foucault uses the metaphor of “capillaries of power” to suggest that power operates at a micro-level through everyday practices, institutions, and relationships. It is ubiquitous.

Rather than being imposed only from above, power works through local, dispersed mechanisms, in schools, workplaces, hospitals, families, and even in how people think about themselves. It functions through rules, norms, expectations, and surveillance that shape behavior and produce compliant individuals.

For Foucault, this makes modern power more effective and harder to resist than older forms of power, because it is not always visible or centralized. Instead, it is embedded in routines and internalized by individuals who come to regulate themselves, often without realizing they are being governed.

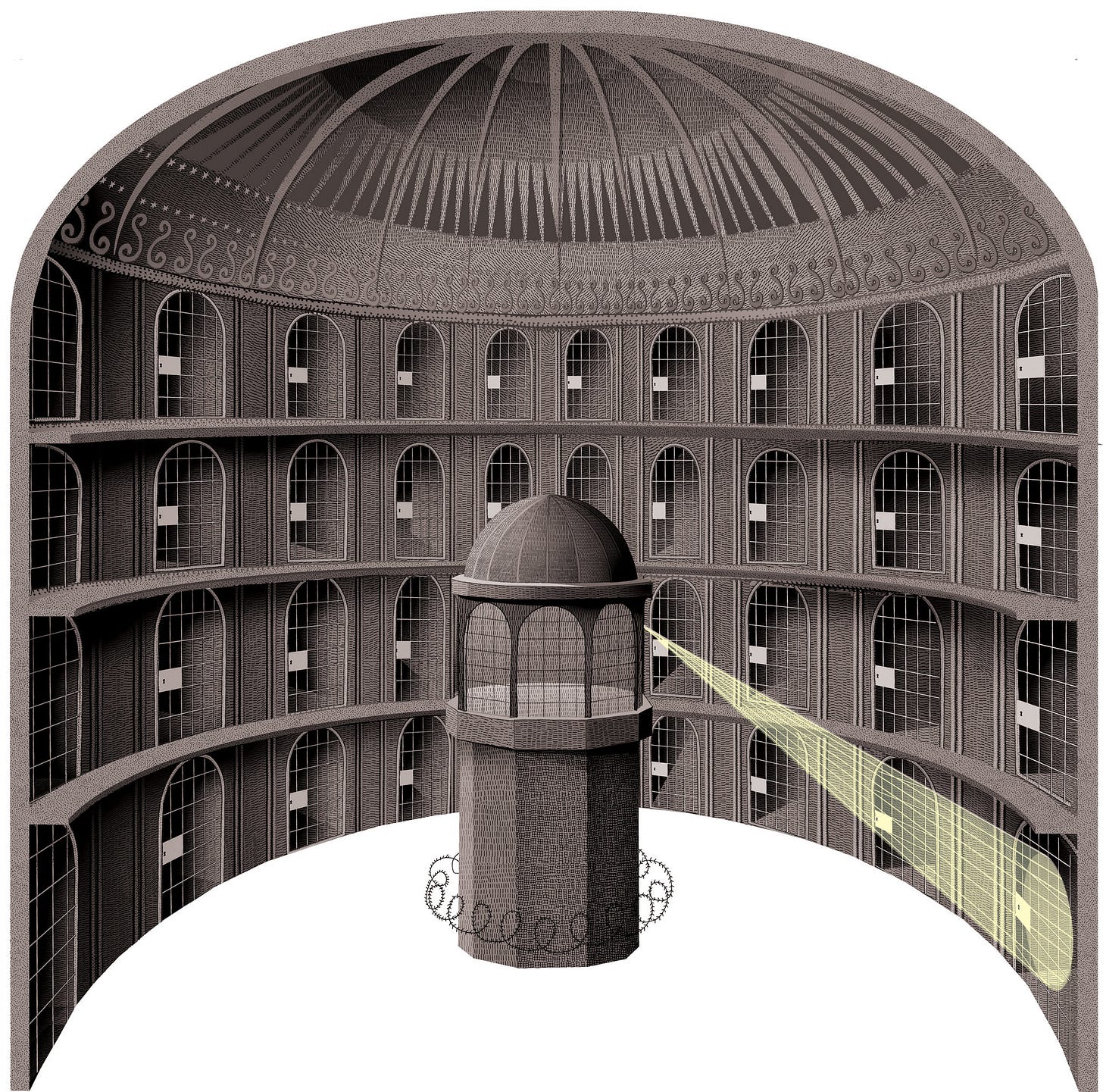

(Foucault uses the “panopticon” metaphor to illustrate how individuals internalize discipline because they believe they might always be watched. Foucault borrowed the idea of the panopticon from the English philosopher and social reformer Jeremy Bentham, who designed it as a model for an ideal prison in the late 18th century.)

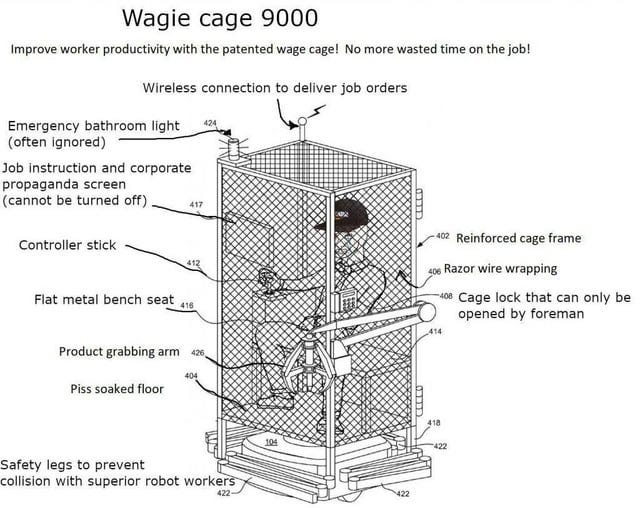

Lets look at how employers are deploying an array of surveillance and performance-tracking systems to discipline workers. For instance, Amazon’s warehouse operations are notorious for their high-tech monitoring of employees.

Each Amazon fulfillment center worker carries a scanner that tracks items picked; the system calculates “rate” (items per hour) and flags those who don’t meet targets. It also logs “time off task” (TOT) whenever a worker isn’t actively scanning packages.

If a worker takes a break deemed too long, the system may automatically issue a warning or termination notice. In one Amazon facility, hundreds of employees (about 10% of staff annually) were fired for failing to meet productivity quotas in a single year, according to internal documents. Amazon confirmed that across 75+ warehouses (125,000 full-time staff at the time), thousands are fired each year solely for productivity deficits, a scale of algorithmic discipline previously unseen.

The process is semi-automated: “Amazon’s system tracks each worker’s productivity and automatically generates warnings or terminations… without input from supervisors” (managers can override in theory, but often do not).

(The wage-cage is a superior metaphor for society than the panopticon. Also, Amazon literally tried to patent this shit…)

This is a direct incarnation of Foucault’s panopticon, workers know that every minute is measured. Indeed, some Amazon employees reportedly avoid bathroom breaks and skip meals to keep their “time off task” low and not trigger penalties.

One warehouse worker said “They’re monitored and supervised by robots… we are treated like robots”. This constant visibility enforces self-discipline: workers hustle to “make rate” under fear of algorithmic punishment.

Beyond warehouses, Amazon also surveils its delivery drivers: it installed AI-powered cameras in delivery vans that watch drivers’ faces and behavior. These cameras (from Netradyne) can detect if a driver yawns, is not looking at the road, or not wearing a seatbelt, and they issue real-time voice alerts and score the driver’s “safety” performance.

Drivers receive weekly “safety scores” and can be reprimanded or lose bonuses if the AI flags too many infractions. Some drivers described feeling “paranoid… always being watched” and even resorting to adult diapers to avoid stopping (since cameras might misinterpret a break or a glance away as an infraction).

Remote office work has also seen a surge in surveillance: By 2023, 96% of companies with remote or hybrid staff said they use software to monitor employees working from home (up from just 10% pre-pandemic). These tools log keystrokes, take random screenshots, or even use webcam monitoring to ensure remote workers stay “productive”.

About 3 in 4 companies admitted they have fired employees based on data from these monitoring tools. This creates an environment where white-collar workers feel the digital panopticon too, some report feeling pressure to constantly move the mouse or avoid any screen idle time for fear of being flagged as slacking.

Such workplace surveillance exemplifies disciplinary power: it makes workers visible continuously, subjects them to quantitative norms, and disciplines their bodily routines (when to take breaks, how fast to move) to fit corporate efficiency standards. There is no traditional violence needed to have an unseen, systematic level of influence over the individual.

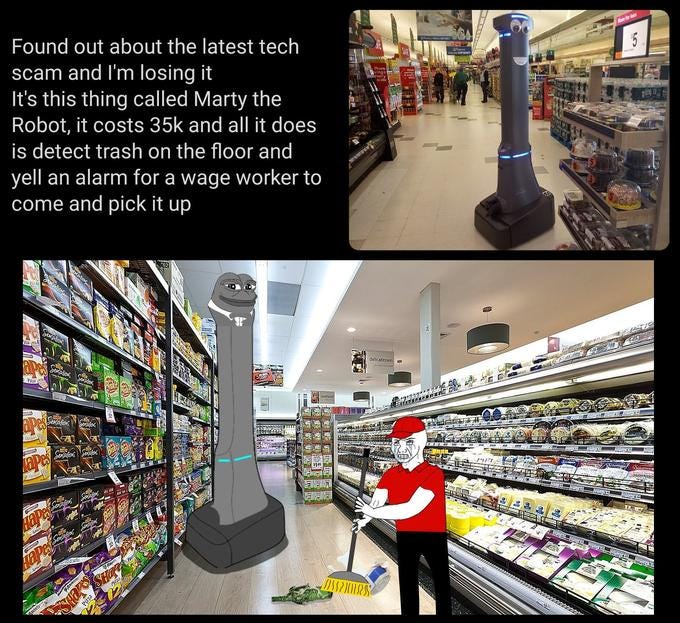

(One of the many humiliation rituals being added to the workplace by big tech.)

This concept of disciplinary power synthesizes quite nicely with surveillance capitalism, as companies have learned to modify user behavior as part of monetization strategies, effectively turning surveillance into a means of control.

(Social media sites don’t just give you content you want to see, they change you to want to see their content.)

A notorious example is the 2014 Facebook “emotional contagion” experiment, where Facebook data scientists manipulated the News Feeds of 689,000 users to show predominantly positive or negative posts. The study, published in PNAS, demonstrated that by tweaking the algorithmic curation of content, Facebook could make users feel happier or sadder and even affect the tone of their own posts.

This sparked outrage when revealed, but it underscores that these platforms not only observe behavior, they also steer it. Google has similarly adjusted designs (like the arrangement of YouTube autoplay, or notification prompts) to increase engagement, effectively nudging users based on surveillance insights.

Zuboff warns that surveillance capitalism moves from “knowing about your behavior to shaping your behavior”. For instance, navigation apps might nudge drivers past certain stores, or Amazon’s recommender system guides consumers to Amazon’s preferred products.

The commodified data allows firms to predict what users might do, but the real power (and profit) comes from using that knowledge to push users toward profitable actions (clicking an ad, making a purchase, spending more time on site).

This is why Zuboff and other scholars see surveillance capitalism as a threat not just to privacy but to autonomy: it entails a “direct intervention into free will”, by exploiting personal data to tune and target messaging at the behavioral level.

For example, real-time bidding can target a known gambling addict with a betting ad at a vulnerable moment, or a social media platform can tweak notifications to keep a teenager hooked. In Foucauldian terms, this infringement on free will is an instance of the individual being constructed by relations of power.

The technofeudal lords bent on accumulating data don’t govern with the threat of violence… Instead, they govern through discipline… through your millions of everyday micro-interactions with technology… and in turn, you govern yourself for them…

Closing Remarks

(Oh… that’s a new phase in exploitation that penetrates our very psyches, eroding authenticity and free will by shaping, controlling and monetizing every aspect of human experience…)

Instead of writing a compeling conclusion that neatly summarises the points made, I thought I would just post that stupid image and then rattle of some insecurities about the article.

I mean, you read the damn article. Do you need me to repeat myself for you? Probably not. I am also drunk off bourbon right now and might not be using my best judgement.

Anyway, I hope you enjoyed reading about technofeudalism, surveillance capitalism and disciplinary power… There are a million other blogs online explaining this stuff, so thanks for reading this one.

I like comparing the three ideas to classical Marxism. I don’t know, maybe capitalism’s biggest haters are best able to identify it’s main features. While on the other hand, maybe capitalism’s biggest enjoyers are too willing to integrate the positive into their definition of capitalism, while ignoring the negative, carving out a new place for things like cronyism as if it is a bug, not a feature.

But anyway, I always find that the haters of a thing have the most interesting things to say about it.

Great post. Particularly this part: "on platforms like Facebook, users effectively “toil” for the platform by posting content and data that Meta monetizes via advertising."

Essentially, Mark Zuckerberg can be thought of as William the Conqueror, one lucky boy who "got in early" and established himself as absolute lord of digital real estate. When people say "start your own platform," that would be like telling the Anglo-Saxon peasantry to "go start their own country." Land is expensive to acquire, and so is digital real estate. It's hard to move people from one platform to another, just as it would be expensive for all the Anglo-Saxons to get on ships and sail somewhere else.

The question is whether there exist "digital nobility" who can rebel against the "digital kings" to create a "digital magna carta."

What would you prefer?

That nurses have to interview for jobs they may or may not get and have little flexibility (that's what my nurse friends do)?

That workers slack off and don't do their jobs? I've talked to Amazon workers and the consensus seems to be "you hustle but it pays better than the alternative."

I'm a remote white collar worker. I do maybe 5-10 hours of real work a week. Nobody ever monitors me or asks about my keystrokes. I make a ton of money, get good performance reviews, and lots of raises and bonuses. But I also you know got an education and spent a long time developing a career so that I'm productive.